by Nicola Mantzaris, White House Photographs Metadata Cataloger

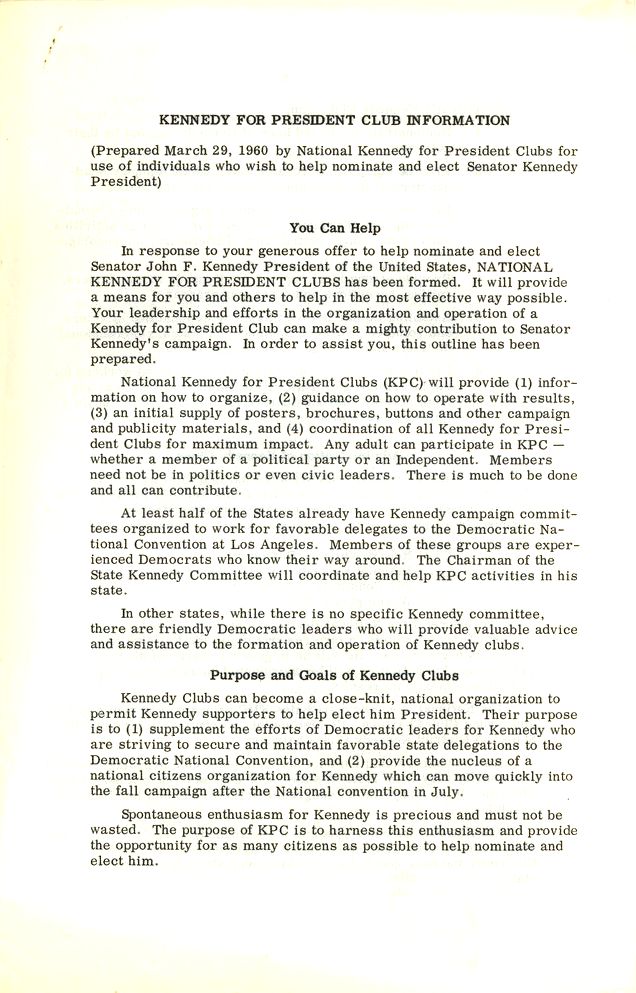

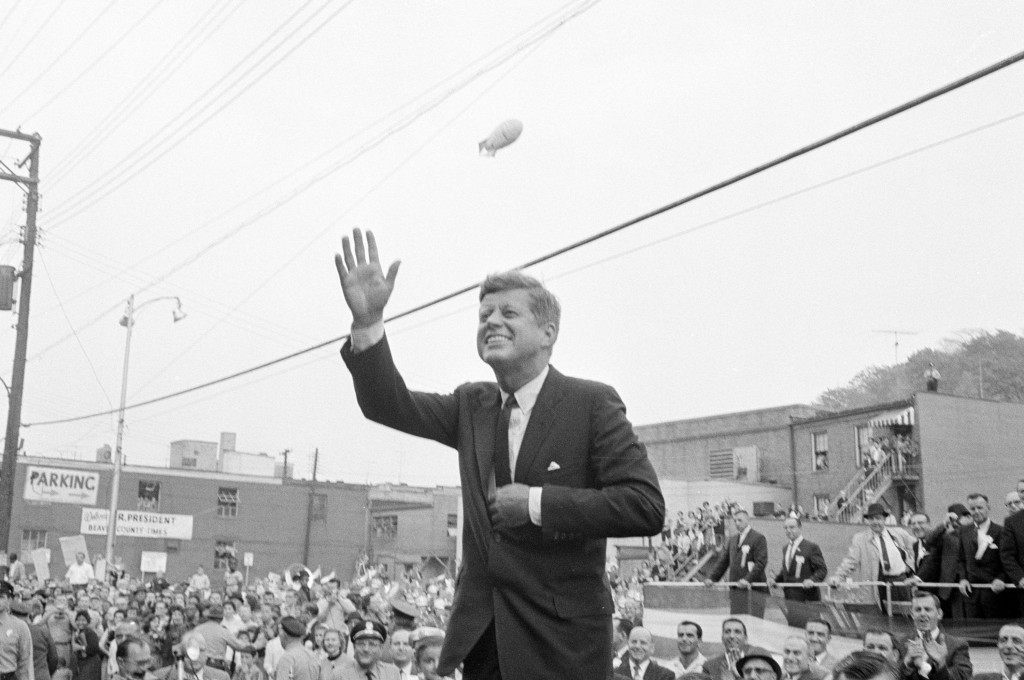

As the 2016 election season gains momentum and we commemorate the fifty-sixth anniversary of the announcement of John F. Kennedy’s candidacy for President of the United States, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Historypin invite you to answer the question: “Did John F. Kennedy visit your town during his 1960 presidential campaign?”

We are pleased to announce that the Kennedy Library has teamed up with Historypin to create a map-based interface called “Mapping JFK’s 1960 Campaign,” giving users a new way to engage with archival materials from Senator John F. Kennedy’s 1960 presidential campaign.

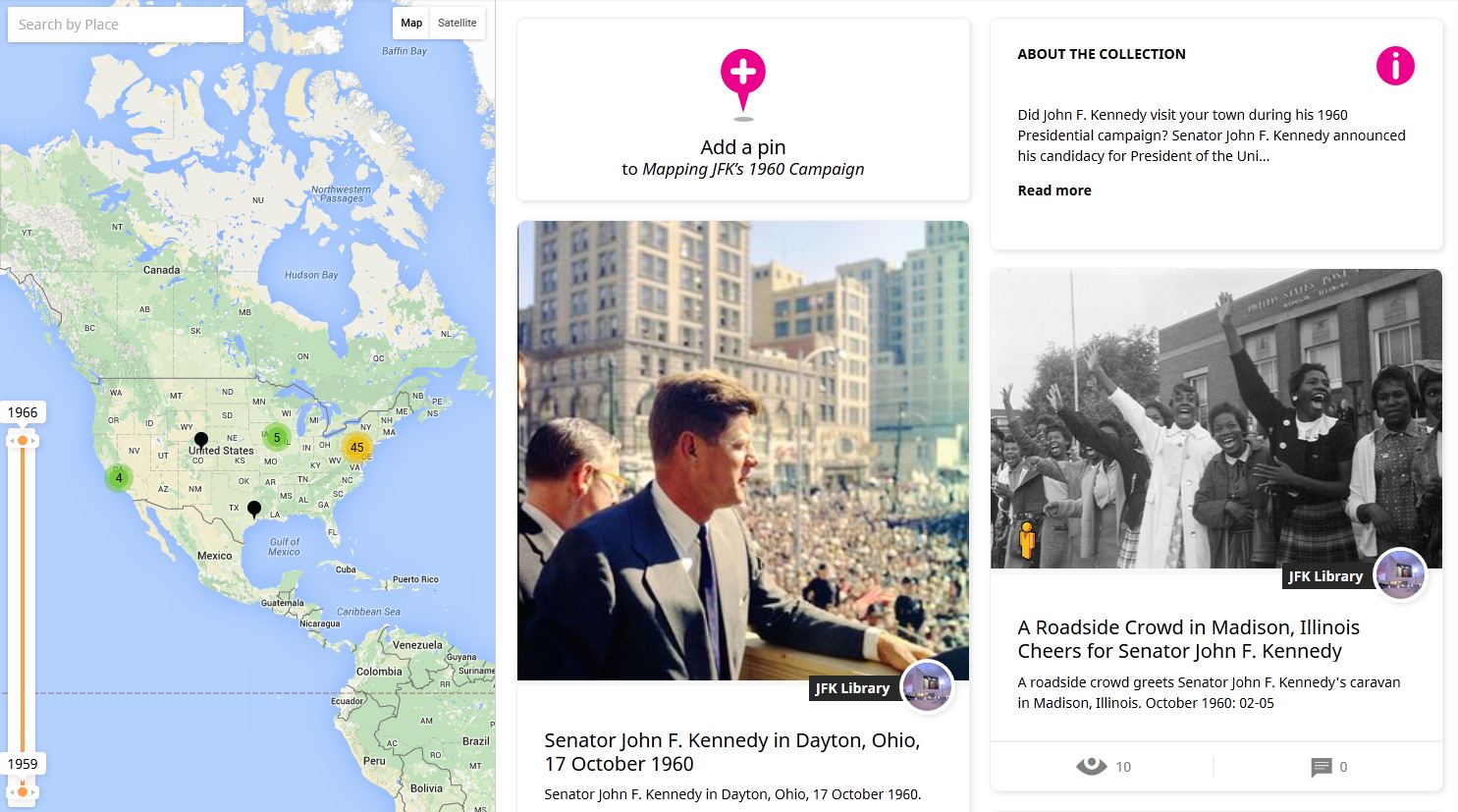

Historypin Collection: Mapping JFK’s 1960 Campaign

Historypin Collection: Mapping JFK’s 1960 Campaign

“Mapping JFK’s 1960 Campaign” is an interactive project designed to encourage visitors not only to follow John F. Kennedy on the campaign trail, but also to make their own connections to the 1960 election year by contributing or “pinning” memories to the Historypin map. It’s free and easy to join the conversation. Simply create a Historypin account and start sharing photographs, videos, and other materials directly from your computer; or, add a link to an image on the Web. Each pin requires minimal information: title, date, and location (e.g., town, region, or street address). Add a personal story or some keyword tags to describe what your pin is about; but always remember to consider copyright and ownership before pinning something to the “Mapping JFK’s 1960 Campaign” collection.

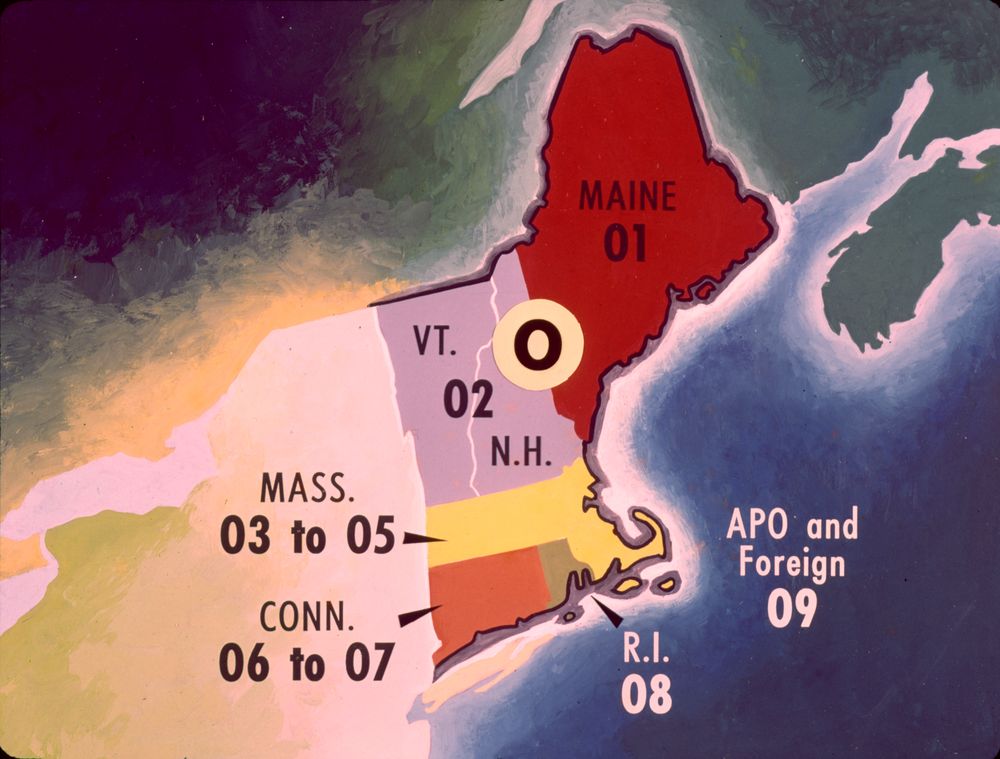

Historypin geocodes digitized content by converting location data into geographic coordinates, which are then positioned onto Google Maps. With Google’s Street View technology, Historypin almost magically brings the past to the present in animated form. If you have an exact address for an outdoor photograph, you can pin it with the Street View overlay and watch the image dissolve from past to present, like this photograph of supporters outside the U.S. Post Office in Madison, Illinois:

For more information, and to watch a how-to video on pinning items to the collection, visit the “About the Collection” page.

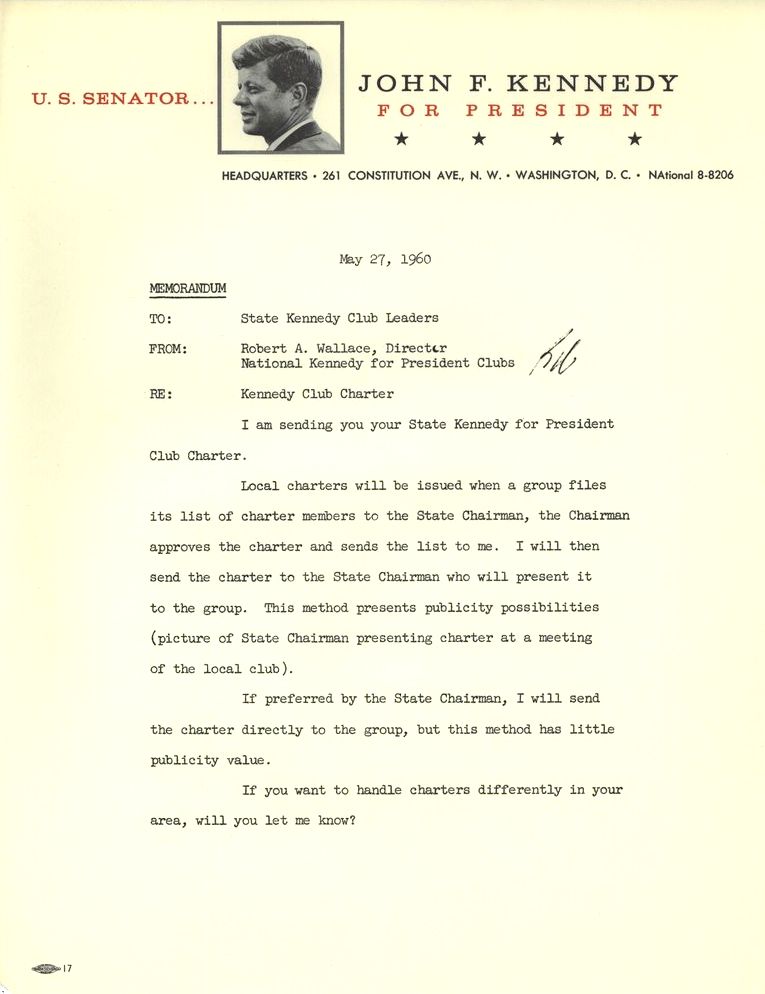

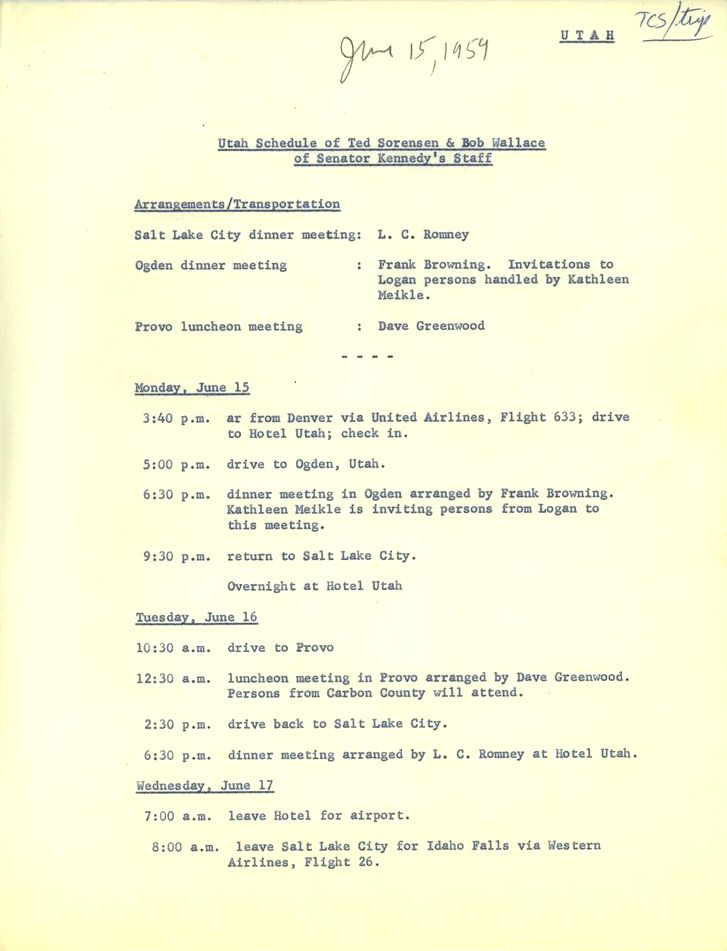

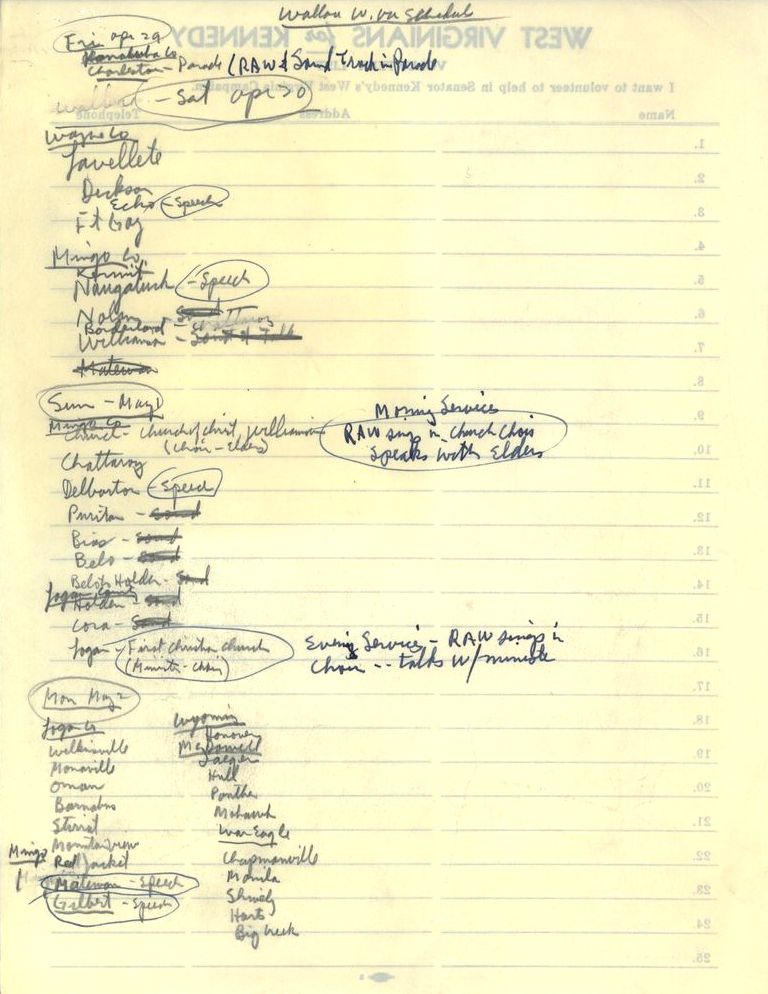

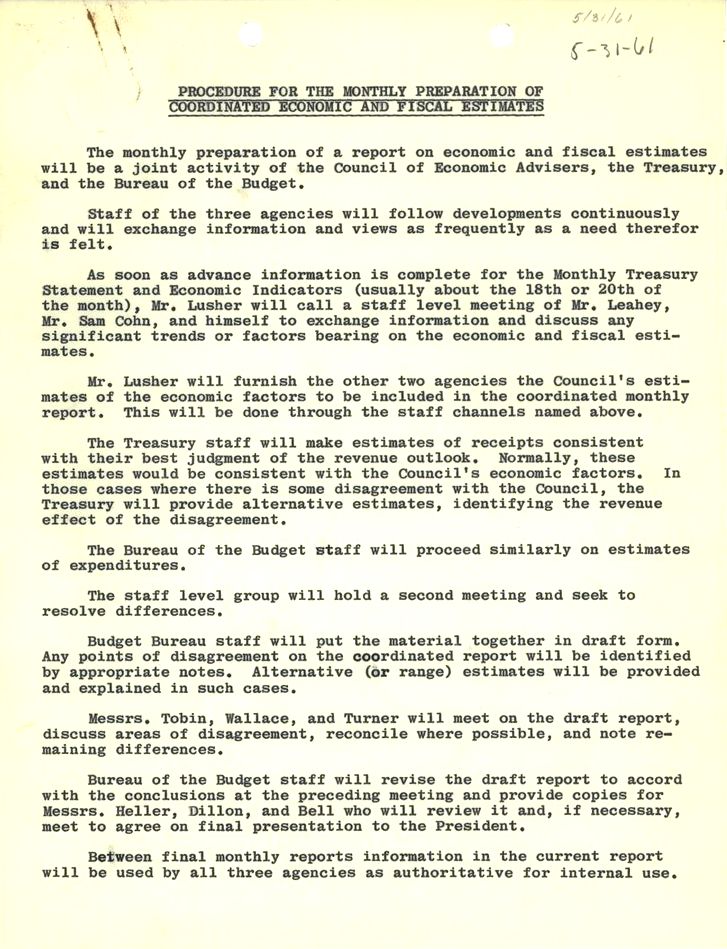

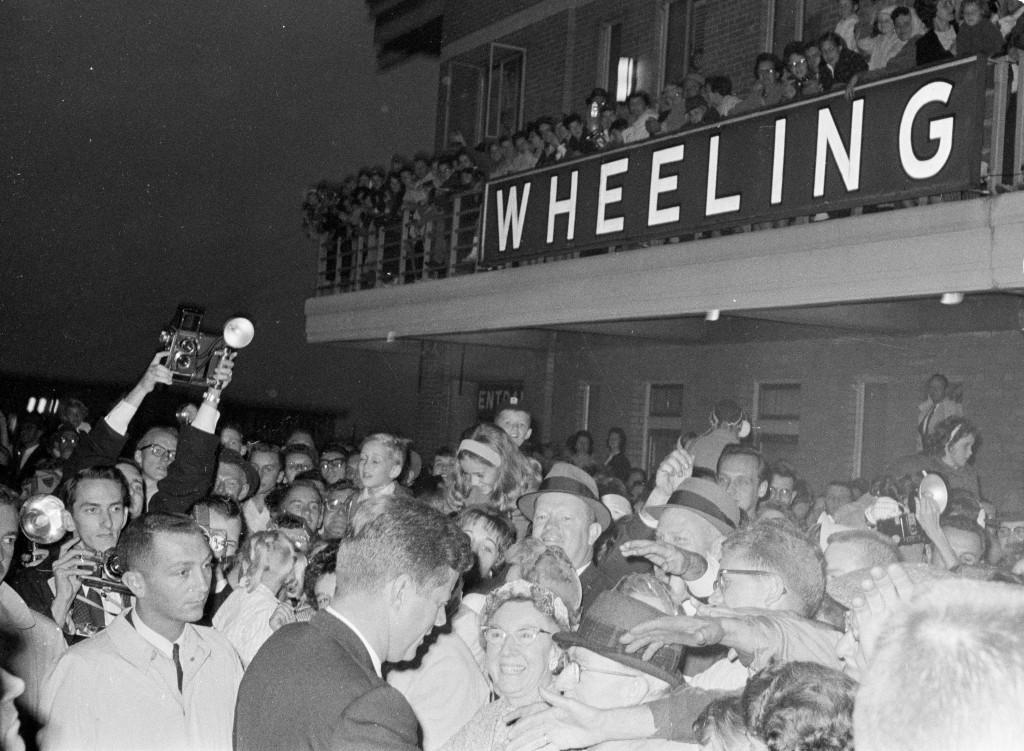

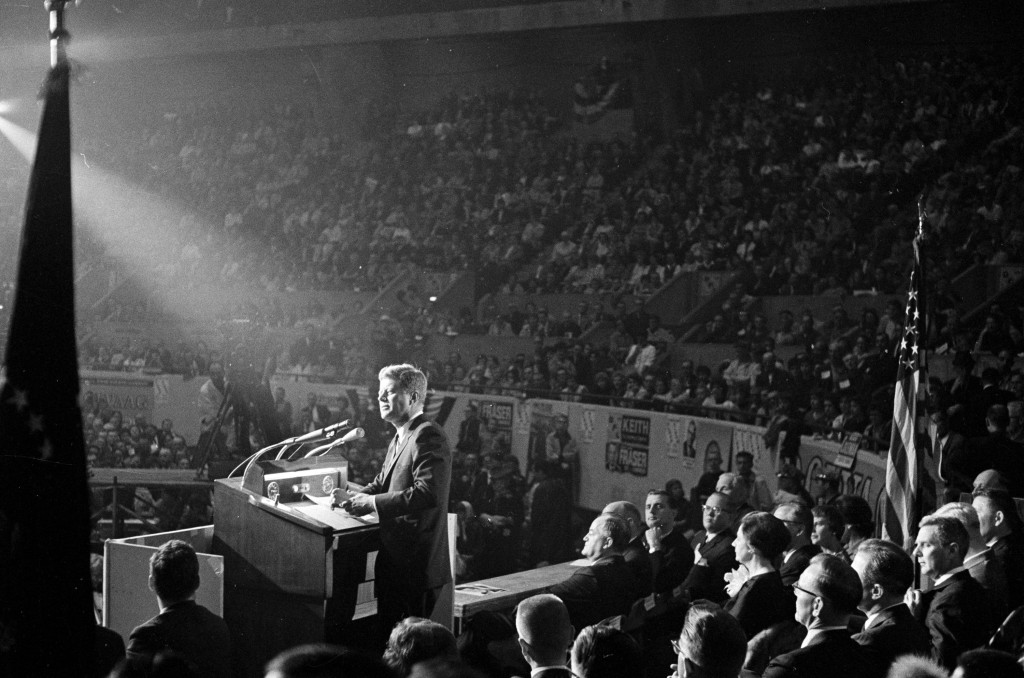

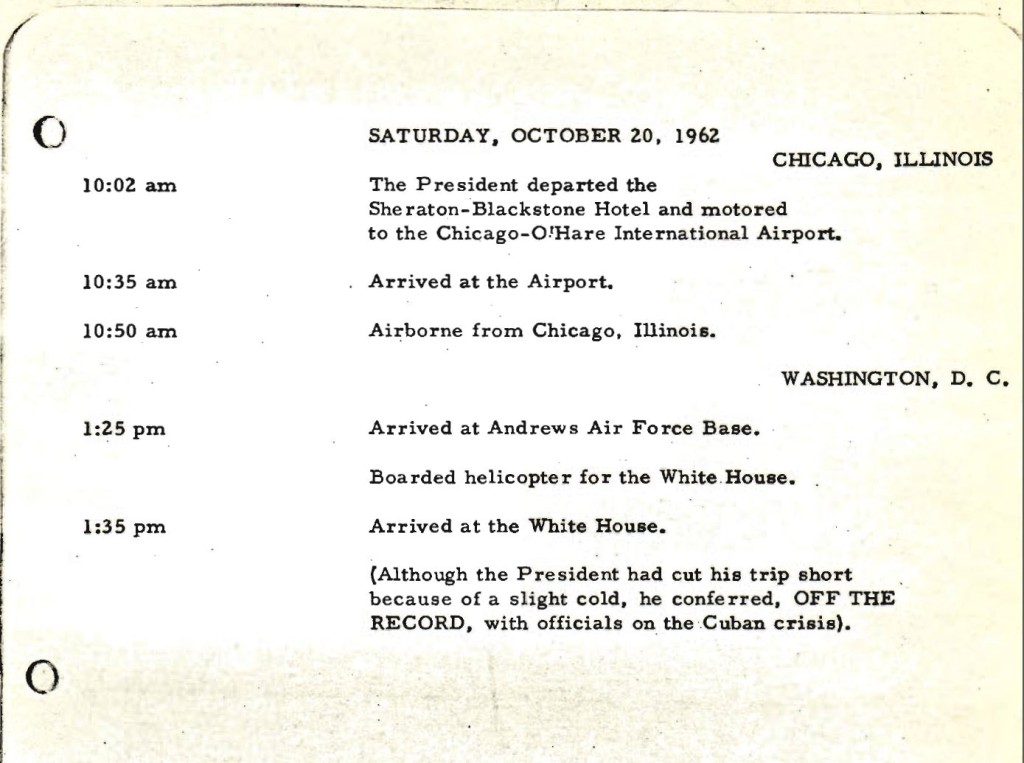

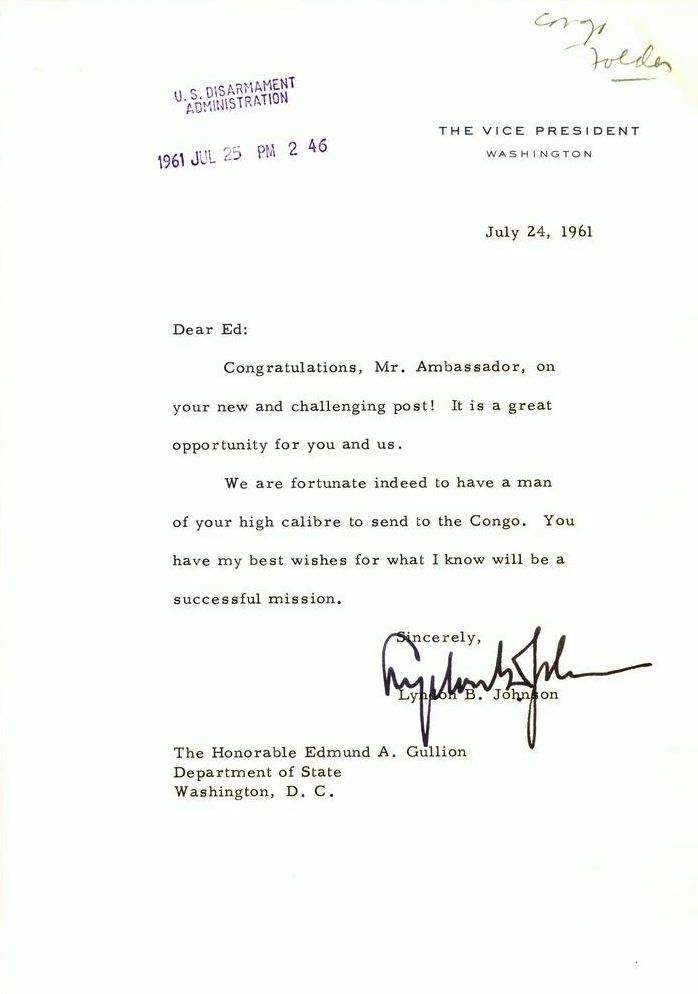

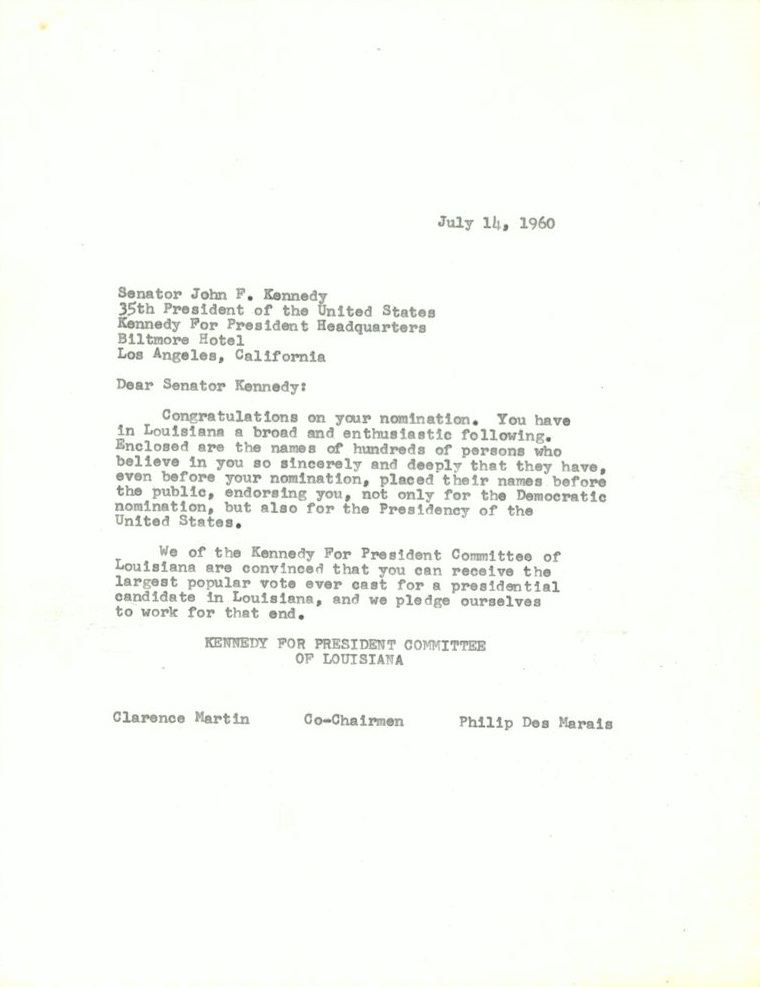

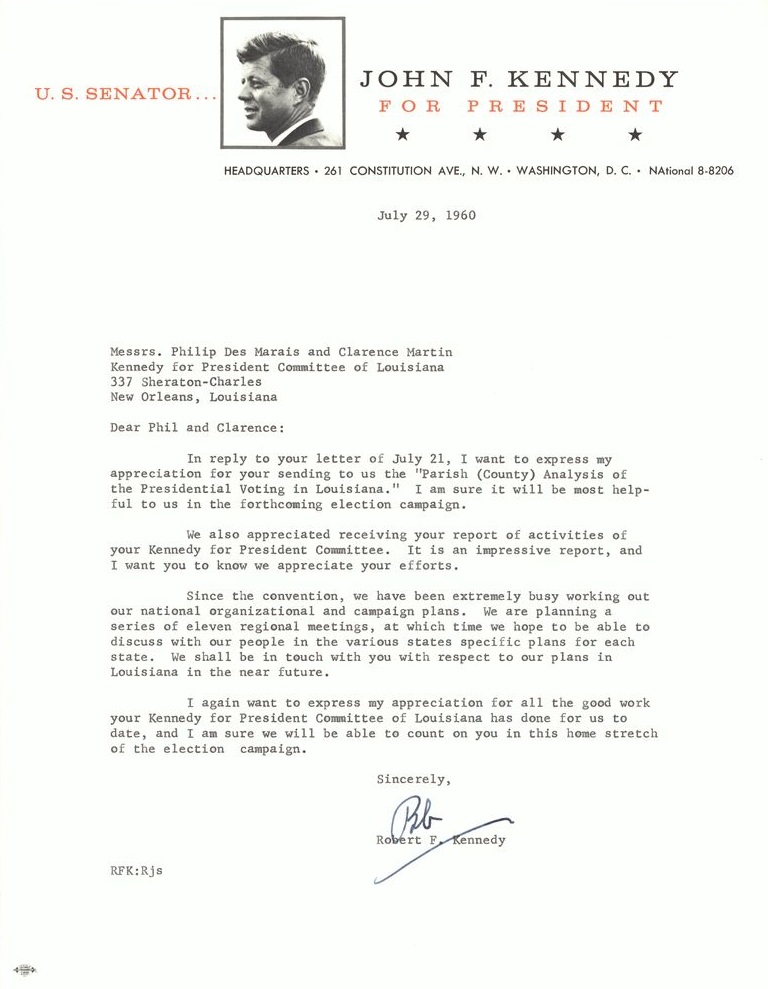

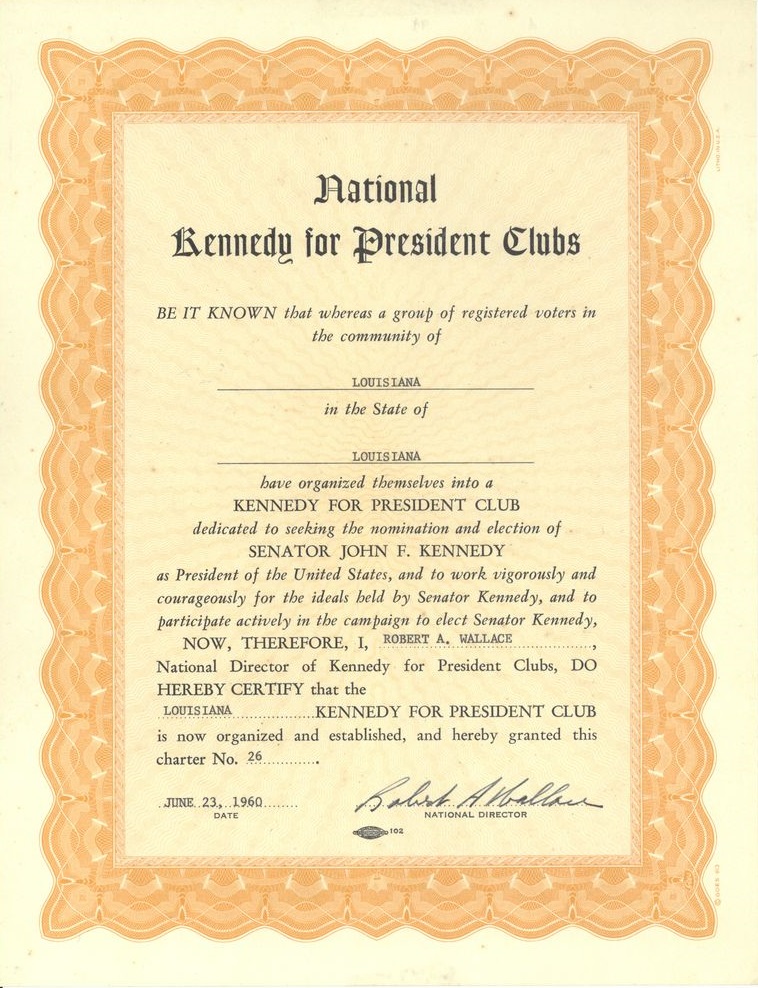

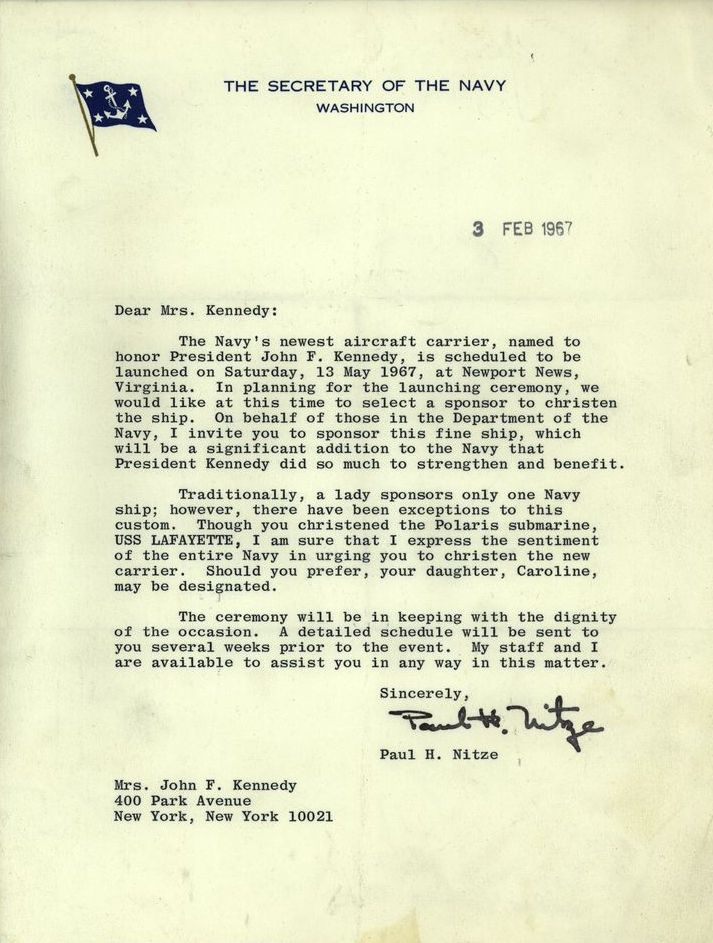

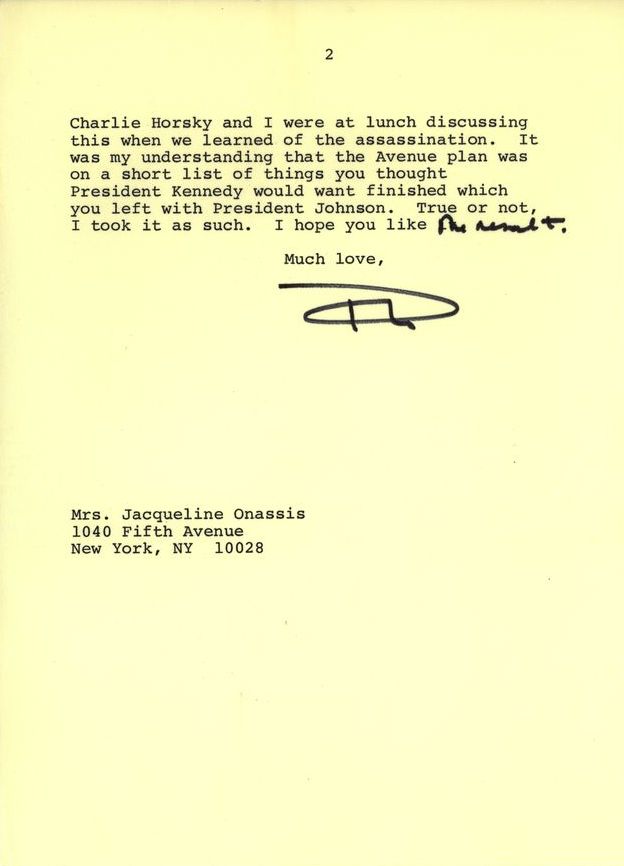

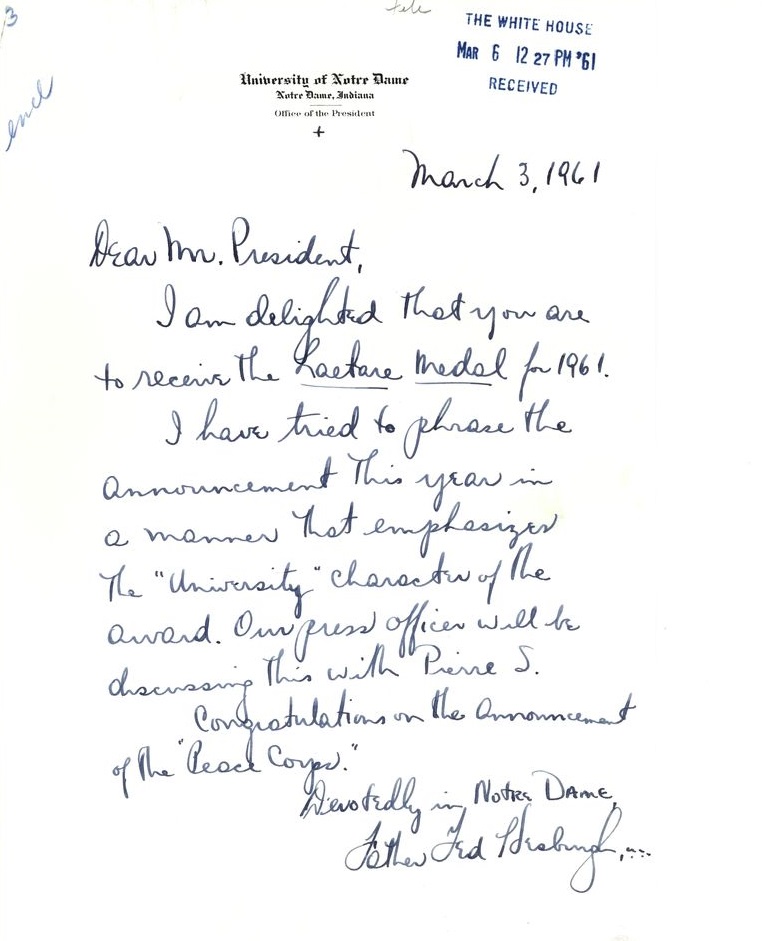

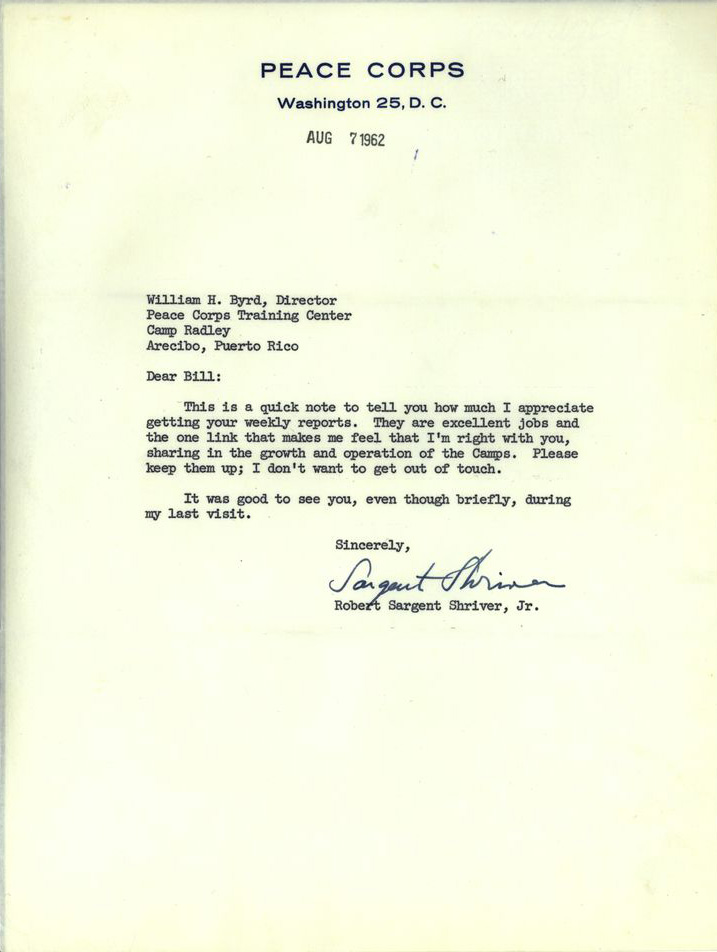

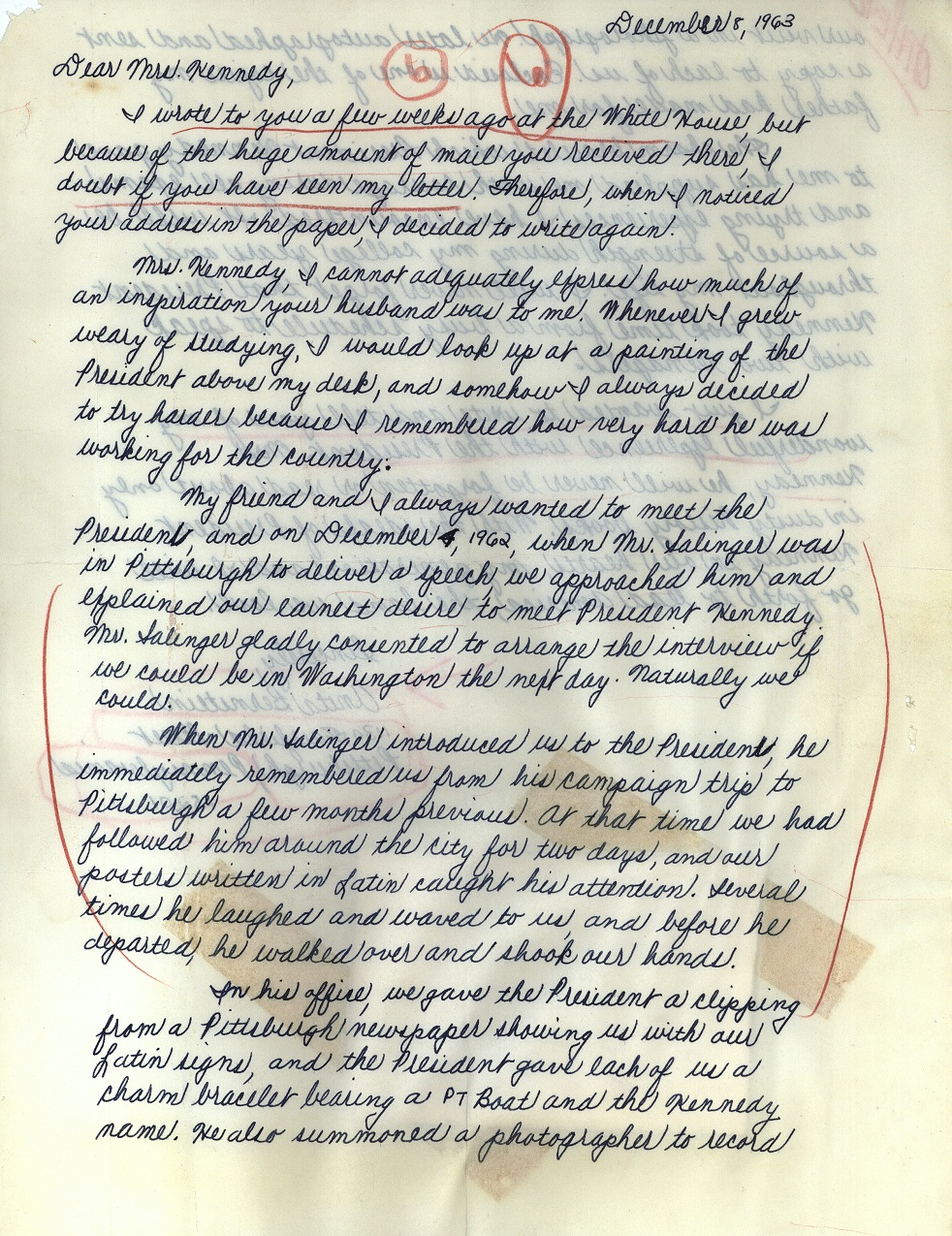

The Kennedy Library also encourages you to explore what made John F. Kennedy’s 1960 campaign the first modern American political campaign. Connect with the local history of Senator Kennedy’s campaign by browsing the Historypin map. Witness the enthusiasm of supporters in Columbus, Ohio. Read a letter from an administrator at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor) who was inspired by Senator John F. Kennedy’s improvised speech proposing the idea of a Peace Corps. Listen to Former Legislative Assistant Myer Feldman discuss the 1960 Wisconsin and West Virginia primaries in an oral history recorded in Washington, D.C. Or, see a schedule of events from the Senator’s visit to Los Angeles, days before he won the Democratic nomination and delivered one of his most famous speeches, asking Americans to meet the challenges of a New Frontier with invention, innovation, and imagination.

SWPC-JFK-C003-007. Supporters of Senator John F. Kennedy Applaud his Arrival in Columbus, Ohio, 17 October 1960

SWPC-JFK-C003-007. Supporters of Senator John F. Kennedy Applaud his Arrival in Columbus, Ohio, 17 October 1960

Letter to Senator John F. Kennedy from W. Arthur Milne, Jr. regarding “Steps of the Union” Address at the Univ. of Michigan

Letter to Senator John F. Kennedy from W. Arthur Milne, Jr. regarding “Steps of the Union” Address at the Univ. of Michigan

Myer Feldman Oral History Interview, 3/13/1966

Myer Feldman Oral History Interview, 3/13/1966

Schedule: Los Angeles, California, 10 July 1960

Schedule: Los Angeles, California, 10 July 1960

Like Historypin, many organizations within the archives and library communities are using geocoding tools to provide innovative ways in which their users may visualize and contextualize complex digital collections. “Mapping JFK’s 1960 campaign” comprises only a small subset of digitized content from the Library’s textual, audiovisual, and oral history holdings. By sharing this content with Historypin, the Kennedy Library hopes to reach new audiences and to deliver to its users a different type of experience.

With your help, we can build a national picture of John F. Kennedy’s 1960 presidential campaign and produce a new research tool for evaluating the timeline and geography of this historic campaign. We hope that you will contribute to the history of your town and share your stories with us!