by Christina Lehman Fitzpatrick, Processing Archivist

We are pleased to announce that the James Saxon Personal Papers are open and available for research. Saxon served as Comptroller of the Currency during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations (1961-1966). As an independent bureau of the U.S. Treasury Department, the Office of the Comptroller is charged with regulating and administering the system of national banks.

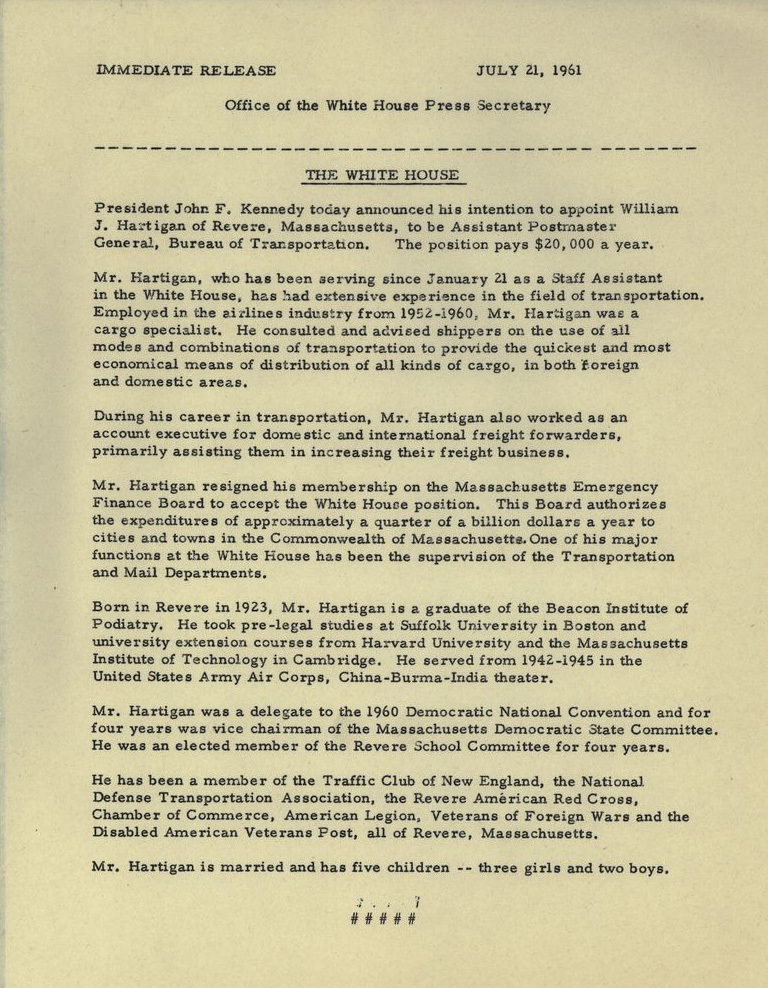

James Joseph Saxon was born on April 13, 1914, in Toledo, Ohio. After studying economics and finance, he joined the Treasury Department in 1937 as a securities analyst in the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. During World War II, Saxon served as Treasury attaché in the Philippines, where he dealt with seized Japanese assets and advised the Army commanders on financial issues. After several years representing the Treasury abroad, Saxon returned to Washington and was appointed assistant to the Secretary of the Treasury in December 1947. He received a law degree from Georgetown University in 1950, then became special assistant to the Treasury’s General Counsel. After a brief stint with the Democratic National Committee, Saxon was named assistant general counsel of the American Bankers Association in 1952. In August 1956, he was hired as an attorney by the First National Bank of Chicago. Saxon was appointed Comptroller of the Currency by President Kennedy on November 16, 1961, and was confirmed by the Senate on February 7, 1962.

Soon after I began processing the collection, I started seeing clues that Saxon was not just another mild-mannered banker. The press dubbed him “that feuding comptroller” and the newspaper headlines blared:

“Saxon, Comptroller of US, Keeps Banking in a Whirl”

“Currency Comptroller is Most Controversial”

“U.S. Comptroller Flaunts Tradition”

“Comptroller Saxon Seems to Enjoy Maverick’s Role”

Who was this government official and how had he caused such an uproar?

I discovered that Saxon’s term as Comptroller was actually quite exciting. He took a much more active role than his predecessors and instituted many reforms in both the agency and the national banking system. These included expanding bank powers, overhauling and streamlining procedures, and lifting restrictions on certain banking products; granting approval to many new banks and branches to encourage expansion and increase competition; creating a network of regional comptrollers with more authority, as well as an international banking unit; adding a new department of trained economists; and raising hiring standards for bank examiners.

(Left) Chart showing the high number of new banks chartered during Saxon’s term. View the entire folder here.

(Right) Saxon discusses his mission and goals in this draft speech. View the entire folder here.

As Saxon explained in one speech (shown above at right):

“When I came into the office of the Comptroller of the Currency, my object was [to] see the commercial banking business inoculated with a spirit of progress, initiative, and innovation. It seemed at the time that unless the commercial banking business could be unshackled and got off dead center, it would continue to stagnate and that the economy and the society would thereby suffer. It appeared that a massive effort should be made to modernize the archaic banking structure and its operational powers and capacity, so as to make it more dynamic and competitive. This program had President Kennedy’s support, without which the controversial forward-looking program which was developed over a period of years would not have been possible.”

Saxon’s innovative approach soon caught the attention of the U.S. Congress, which was worried that he was approving charters for too many new banks. After a string of high-profile bank failures, Saxon was called to testify before Congress and defend his policies. He also butted heads with the other regulatory agencies (most notably, the Federal Reserve and the FDIC) while asserting the authority and independence of the Comptroller’s Office. Even though several of his regulatory initiatives were later overturned by the courts, Saxon left a lasting mark on the banking industry that can still be seen today.

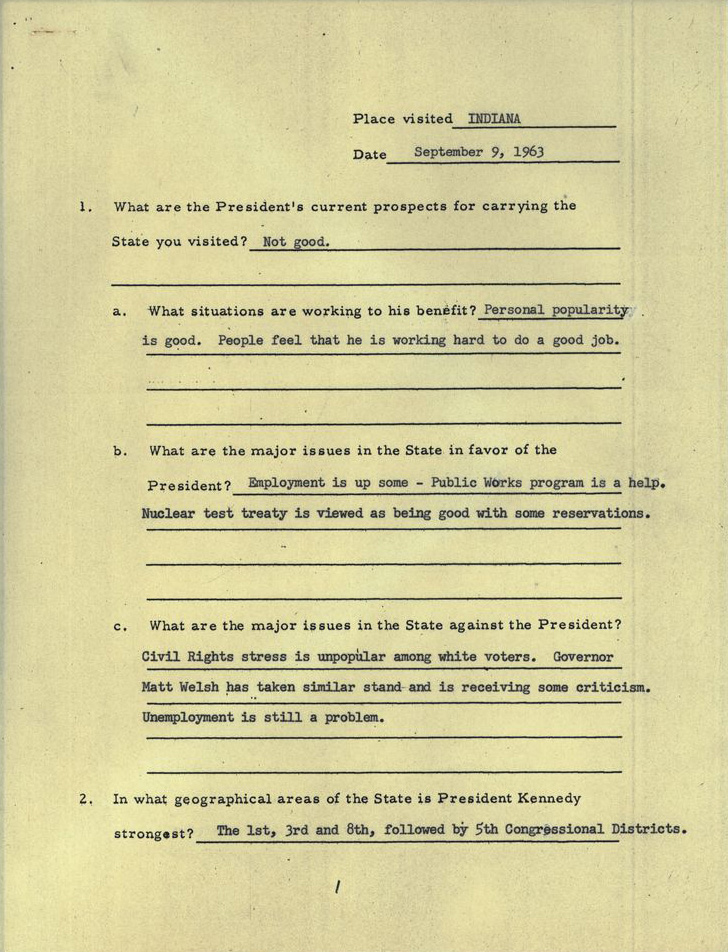

(Right) Sample question from the briefing book Saxon used to prepare for the Congressional investigation into national banks. View the entire folder here.

(Below) Memo from Saxon to G. d’Andelot Belin, General Counsel for the Treasury Department, expressing his displeasure at perceived encroachment on the Comptroller’s authority. View the entire folder here.

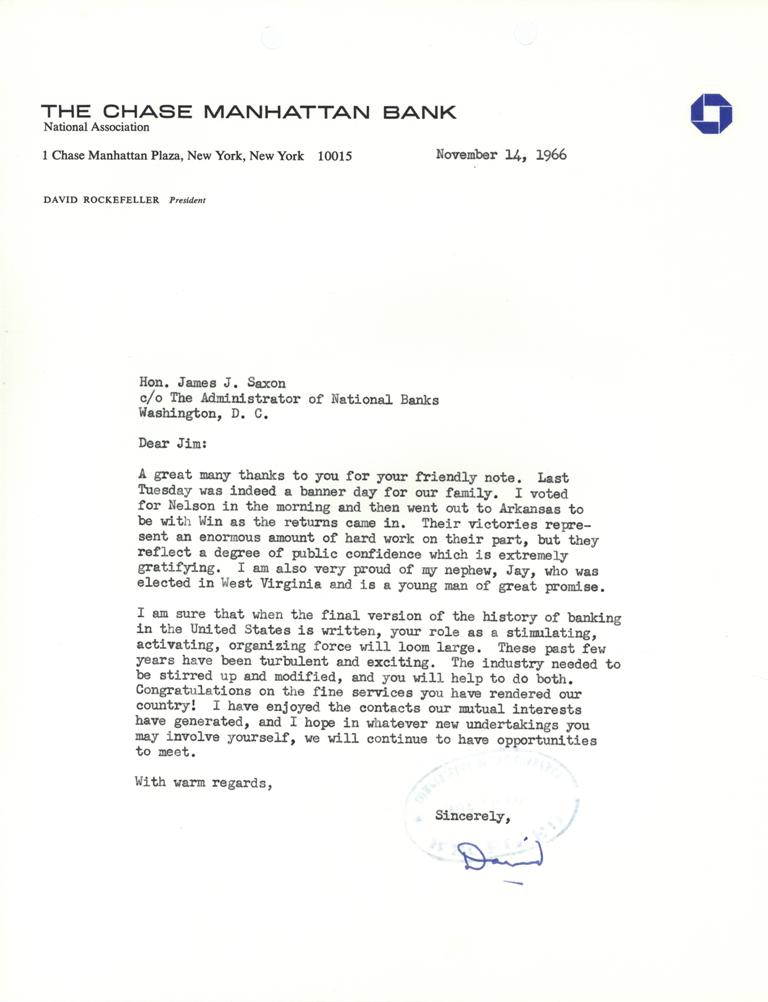

Upon his resignation at the end of 1966, Saxon received an outpouring of congratulations from bankers around the country. David Rockefeller of the Chase Manhattan Bank wrote:

“I am sure that when the final version of the history of banking in the United States is written, your role as a stimulating, activating, organizing force will loom large. These past few years have been turbulent and exciting. The industry needed to be stirred up and modified, and you [helped] to do both. Congratulations on the fine services you have rendered our country!”